It’s become common to think about cultural change the same way we think about biological evolution—so common that it may obscure whether the comparison really works. Though there remain many questions yet to answer about biological evolution, it’s a process that’s well-understood. We know, in great detail, how variations emerge, how they’re passed on hereditarily, and how natural selection and other forces push organisms toward change. Evolution is integrated with almost everything else we know about biology.

It’s been much harder to pin down the exact workings of how ideas change, which has led some scientists to wonder just how deep and literal is the connection between biological and cultural evolution. The greatest skepticism has been aimed at the idea of memes, ideas that are purportedly the individual units of cultural evolution, paralleling the role of genes in biological evolution. Richard Dawkins coined the term meme and proposed the analogy in 1976, in his famous book The Selfish Gene. Some researchers tried to extend the analogy, arguing that the study of memes was a bona fide field of science. But after many years, “memetics” remains stuck at square one, unable to overcome some existential questions: What is (and is not) a meme? Where does one meme stop and the next start? How do memes accumulate errors, the analog of genetic mutations? Until would-be memeticists can answer those central questions, memes are appropriate informal descriptions for online trends, not for rigorous studies.

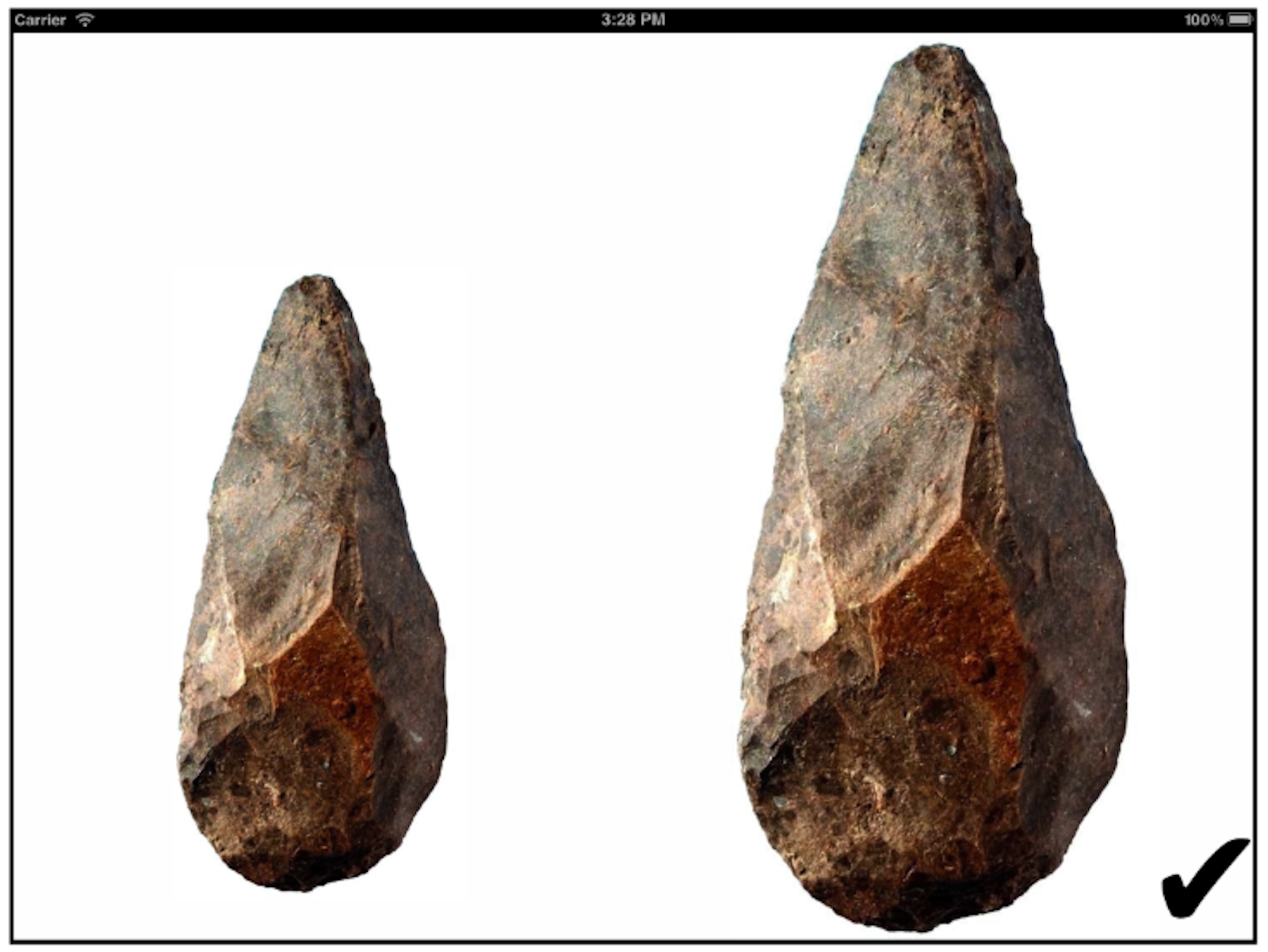

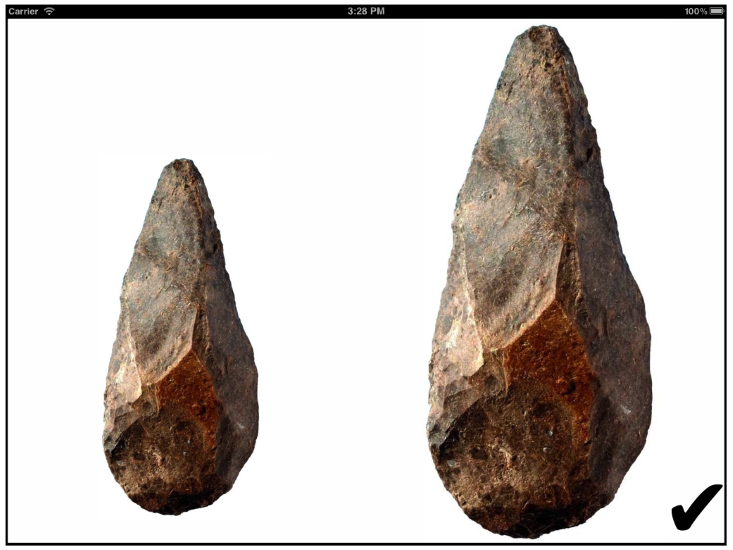

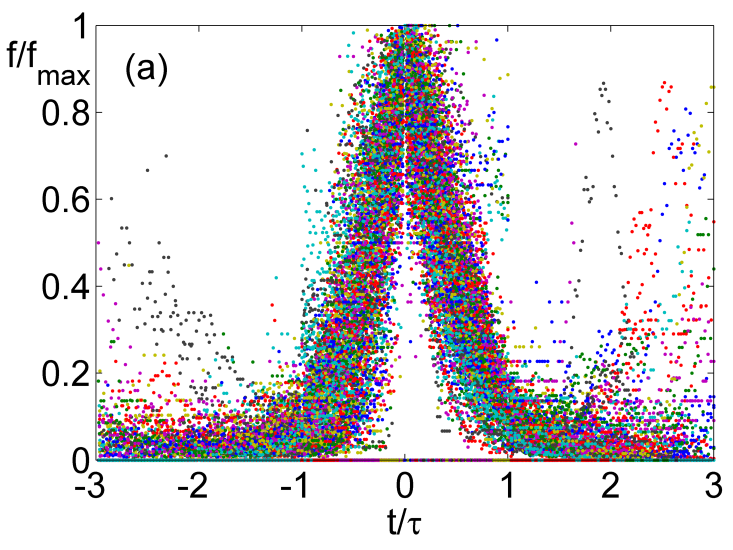

Despite the apparent flop of the meme as science, the study of cultural evolution as a whole has borne fruit. Lacking a rigorous description of the building blocks of cultural evolution (e.g., the meme), the field has focused more on the big-picture view of how certain specific kinds of ideas move through groups of humans. For instance, one surprisingly active research thread looks at what caused Stone Age handaxes to change in size over time. One British study had participants adjust the handaxes on an iPad to match the previous participant’s image. (Why use modern technology to simulate the ancient kind? “Ideally…participants would be asked to create a new Acheulean handaxe by faithfully copying the previous participant’s handaxe,” write the researchers. “However, Acheulean stone knapping is both dangerous and difficult, and finding enough participants who would be both willing and able to knap handaxes would be a challenge.”) The researchers found that one person’s random error in copying the tool could become further exaggerated by subsequent participants, sometimes yielding tools that were gigantically bigger than the original. The study’s “cultural mutation model” thus generated a good analog of genetic drift, the same phenomenon behind the molecular clock used to measure, for instance, the evolutionary separation between chimps and humans. Other researchers argue that this type of drift revealed in modern experiments is the same reason why actual stone spear and dart tips did shrink over time among people who lived in what is now the U.S. over 10,000 years ago. (This agrees with another experiment from the iPad team, who found that “reductively” shaped artifacts like handaxes are more likely to shrink than grow over time: You can improve an oversized tool by knocking off more stone, but once it’s too small, there’s no way to fix it.)

In modern times, we have similar forms of cultural evolution, though it doesn’t come out in the way we knap handaxes. One of the better places to see how tastes change nowadays is in baby names, which have been faithfully recorded for decades in many countries. One study from the University of Pennsylvania concluded that a name is boosted when a similar-sounding name becomes popular; when Karen booms, Katie is likely to come with her. The effect even extended to notorious hurricanes, which can also lift the popularity of similar names. Two British researchers found that in the latter part of the 20th century, American baby names hit a dramatic increase of inventiveness—effectively an increase in the mutation rate—which led to different regions of the country experiencing relatively fast cultural drift in different directions. An international team claimed to show why so many names dramatically rise and then fall in popularity: Parents tend to pick pleasing names that they encounter, and many of them end up choosing the same rising-in-popularity names, unaware of just how common they are. When the kids get to around school age, the popularity becomes clear, and parents run far away from the overexposed names.

Handaxes and baby names are just two examples of where researchers are showing how ideas flow and mutate between people. Alex Mesoudi, an evolutionary anthropologist and one of the researchers behind some of the handaxe studies, points out that there’s other strong work on the evolution of languages, folktales, modern technology, and religion, among other fields.*

So the big idea of the meme is essentially stuck in its existence as a pop-culture meme. Considering the brain-boggling complexity of the human brain, it may be too much to expect one grand unified theory of how ideas are absorbed, mutated, and communicated. (Compare the success of the Human Genome Project versus the failure of the Human Brain Project to even get off the ground.) Meanwhile the real study of cultural evolution proceeds, one modest, solid step at a time.

* The post was updated on May 21, 2015, to include the clarification that researchers have successfully studied the evolution of many cultural elements beyond handaxes and baby names.

Amos Zeeberg is Nautilus’ digital editor.